|

|

|

|

|

I was in the queue, still in school uniform, in Willy Elliff’s fish and chip shop in Flockton, Yorkshire, when somebody rushed in to say that President Kennedy had been shot. I remember watching the first Moon landing with a very excitable French au pair girl in a de-licensed pub in Cambridge (don’t ask) and I clearly remember the warm feeling of seeing my first piece of freelance journalism gracing the pages (well, part of a column) of the Yorkshire Post.

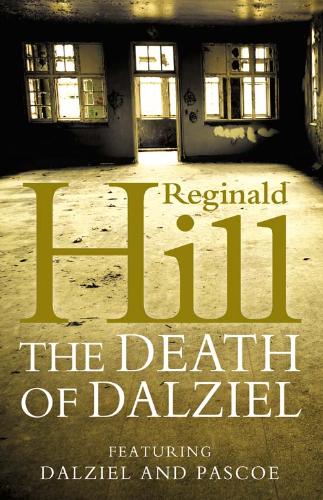

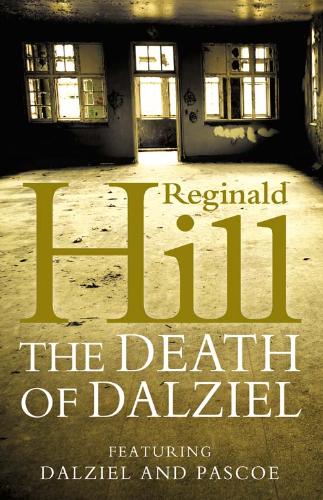

But I can’t remember the first Reginald Hill book I read, and that has been bugging me of late, ever since I realised that the forthcoming TheDeath of Dalziel was the 21st novel in the series.

Now twenty-one books featuring the same characters, over a period of 37 years is quite an achievement for a writer, not to mention a strenuous test of loyalty and stamina for the reader. Personally, I can think of only two other writers who have commanded my devotion, respect and failing eyesight for that mystical 21-book marathon: Michael Innes and John D. MacDonald, though both wrote many other books outside of the series-hero envelope.

As has Reginald Hill. In fact until I started this little homage, I hadn’t realised just how many books he had written since his first tentative steps into crime fiction around 1969. When I suggested to him that it might be 48 novels, he said: That sounds very reasonable. I counted religiously till I got to ten, then in a more secular fashion till I got to 20, and after that I lost interest in keeping a tally. I mean, if twenty doesn’t mean you’re a real writer, then what number does?

Even my very basic skills in mathematics tells me therefore, that the Dalziel and Pascoe series for which he is best-known, is in fact only about 44% of his output, not counting short stories (at which he’s been known to turn a deft hand). So could it be that I discovered Reginald Hill before I discovered “the best detective duo in the business” (as one esteemed critic once wrote)? On reflection, I think I did.

I am pretty sure now that my first dip into the Hill fiction fountain was round about 1978 with the paperback edition of A Very Good Hater, a thriller about taking revenge on a former SS officer twenty-five years after the war (shades of Geoffrey Household perhaps, but well before The Odessa File). Then, by chance, I came across a copy (ex-libris Magdalene College School, Oxford) of Fell of Dark, an interesting piece of Hill-related trivia on several counts. Apart from being an excellent suspense novel in a lovingly-described Cumbrian setting, it is also written in the first person and starts with the prophetic (for Reg) lines: I possess the Englishman’s usual ambivalent attitude to the police. They are at once protectors and persecutors. It was also, I subsequently discovered, Reg’s first completed novel, though his second to be published, in 1971, after his 1970 debut A Clubbable Woman which marked the birth of Dalziel and Pascoe.

So by 1978 I had discovered Reginald Hill, but not Fat Andy Dalziel nor Peter Pascoe. Ironically, I was also the proud owner of four slightly surreal and very funny thrillers – Red Christmas, Death Takes the Low Road, Urn Burial and Castle of the Demon – by someone called Patrick Ruell, never once suspecting that this was one of Mr Hill’s alter-egos.

I was unable to avoid the magical world of the Mid-Yorkshire Constabulary much longer though, for 1978 saw the publication of A Pinch of Snuff, which dealt with ‘snuff’ films rather than ground tobacco and was, judging by the reviews and publicity, quite a hot topic back then. There was a review of the book in one of the Sunday papers which was enough to persuade me to go and buy it and from then on I was hooked.

*

Reginald Hill was born in Hartlepool in 1936, the son of a professional footballer who played for various Third Division North teams, including the Hartlepool ‘Pools’. When he was three, the family moved coasts, to Cumbria, where he and his wife and numerous cats, live today.

National Service claimed him from 1955-57, more specifically the Border Regiment, with whom he served in Gottingen in Germany making sure the drapes on the western side of the Iron Curtain were defended. (It was) very tedious except when Suez and Hungary blew up (in 1956) and it became very terrifying as rumours flew that we were off to the Canal in the morning unless the Red Army came over the East German border first. Happily neither happened and Lance-corporal Hill was returned to civilian life more or less in one piece.

Swapping one medieval institution for another, the de-mobbed Hill went to Oxford to read English Literature and then became a teacher, initially in the wilds of Essex but then back “oop north” to Doncaster Teacher Training College to teach teachers.

Whilst teaching in Doncaster he finally got around to putting down on paper some of the stories which had buzzed around his head and although second in terms of writing, A Clubbable Woman, with its scenic backdrop of rugby clubs, northern women and in particular one very large policeman. was taken by publishers Collins for their legendary Crime Club list in 1970. (Collins insisted on the full ‘Reginald’ rather than the more matey ‘Reg’ on the titles page, following the party line that they did not, after all, publish ‘Ag’ Christie.)

The Hill fiction factory was in full flow, and still is, at a rate of a new title roughly every nine months: crime novels, thrillers, spy thrillers, historical swashbucklers and even science fiction under the names of Reginald Hill, Patrick Ruell, Charles Underhill and Dick Morland flocked south to London to be published by Collins and also Hutchinson, Faber and Methuen. For his first ten years as a published author, I estimate a staggering output of 18 novels and no doubt an England cricket score’s worth of short stories plus An Affair of Honour, a play in the BBC’s 30-Minute Theatre series starring Nigel Davenport and Harry Andrews. As this was 1972 and pre-video tape, sadly no recording survives.

When was it, I asked him, that the Dalziel and Pascoe books became, as Ruth Rendell once said of Chief Inspector Wexford, his ‘bread and butter’? It wasn’t till the early 1980s after I’d gone full time (author) that I really started paying attention to sales figures. Even when it became clear the D & P series was my banker, I refused to write one a year but kept on going wherever my imagination took me. Steadfast, eh? Or maybe stupid! But as I’m sure Ruth would agree, just to write about one set of characters all the time would drive me mad.

The determination to follow his imaginative star has taken Reg Hill not only to the heights of the British police detective novel, but into spoof chase thrillers (as Patrick Ruell), into the worlds of spies, assassins, Freemasons, Knights Templars and World War I (as both Hill and Ruell), into bleak, dystopian sci-fi (as Dick Morland) and into the 17th century (as Charles Underhill) to chronicle the adventures of Captain Carlos Fantom, a character mentioned all-too-briefly in Aubrey’s Brief Lives, one of Reg’s favourite books.

Fantom, a Croatian soldier of fortune, supposedly ‘spoke thirteen languages, was very quarrelsome and a great ravisher’ though Hill once convinced an unsuspecting journalist that he had played Left Back for Everton in the mid-1990s.

Such an output may suggest something of a grasshopper approach to writing, but there are long, solid strands of continuity which are probably the backbone of Reg’s career. His first Dalziel and Pascoe book was published by (William) Collins’ Crime Club and though the Crime Club fell by the wayside ten years ago, his twenty-first is still with (Harper) Collins. There are not that many authors about which that can be said these days.

For more than 21 years, he had the same editor, Elizabeth Walter (who famously discovered Lovejoy and Fitzroy Maclean Angel and, infamously, turned down Inspector Morse!) and for over 30 years, he’s had the same agent, Caradoc King at A.P. Watt, once he realised that my powers of haggling were on a par with George Dubya’s powers of elegant self-expression.

Neither has he been tempted away from rural Cumbria (surely a tautology?) for the bright lights of, say, Leeds or tax-exile in Jersey, nor, apart from the one BBC play (and one sketch for the Dave Allen show!), has he responded to the siren call of writing for the television or film screens. Reginald Hill was settled as a novelist and seemed set on staying that way.

One of his thrillers, The Long Kill, originally published under the Ruell pen-name in 1986 was made into a TV movie in America in 1993 although the action was transferred to New Mexico and the title changed to The Last Hit.

It starred Bryan Brown and the wonderful Harris Yulin and was directed by Jan Egleson, who acted in The Friends of Eddie Coyle before turning director on adaptations of Tony Hillerman’s Coyote Waits and Simon Brett’s A Shock To The System.

But if Hollywood called asking for more, Reg ignored them. And it seemed almost inconceivable to those watching the crime fiction scene in the late Eighties and early Nineties that the Dalziel and Pascoe books had not yet made it on to television. It was, after all, the decade of the TV detective. Marple, Dagliesh, Wexford, Poirot, Morse and, in 1992, Frost, were all established audience-pullers and others such as Resnick and Sharman had at least been sampled.

There had, as Reg puts it, been many “sniffings around” the rights to the Dalziel and Pascoe books but it was not until 1993, 23 years after their birth, that the dynamic duo got the full Yorkshire Television treatment – and what a treatment!

A Pinch of Snuff was the book chosen for the pilot film to introduce the series and the larger-than-life character of Andy Dalziel and his politically correct alter ego Peter Pascoe. So far, so good you would have thought, but then Yorkshire TV threw in a plot twist not even Reginald Hill would have used (though Patrick Ruell in his more mischievous earlier days might have).

Dalziel and Pascoe were to be played by the comedy duo Hale and Pace, then under contract to ITV, even though neither Gareth Hale (Dalziel) or Norman Pace (Pascoe) had much, or any, acting experience. It showed.

And here is where I declare an interest, for I was one of the hacks lined up by YTV to adapt subsequent books as screenplays for that projected first season. Yes, I was the man who adapted Reginald Hill’s An Advancement of Learning for two stand-up comedians who, to be fair, were the first to admit they couldn’t act. Except I wasn’t, because after Reg saw the pilot film of Snuff he refused to give permission for any other titles to be adapted and I, and the other hacks, were all fired before we’d actually been given contracts.

Was I bitter about this sudden curtailment of my scriptwriting career? Not really; you see, I’d seen the pilot episode as well - at a preview screening for cast and crew in London where there were lots of brave luvvy faces because everyone in their luvvy hearts knew that the first episode had not cut the mustard and we all suspected that there would not be a second episode.

The cast and crew dispersed to the four winds. Hale and Pace went on to a lucrative tour of Australia, the producer moved on to work on Taggart and I was offered development work on a new drama series for Yorkshire TV which was fun and well-paid, but which never came to anything. The actual pilot was finally shown on ITV in 1994, late one Saturday night with little pre-publicity and up against Match of the Day on FA Cup Final Day. Even with the current proliferation of material-starved digital channels, I don’t think it has ever been repeated.

Meanwhile, Dalziel and Pascoe were consigned to the seventh or eighth circle of television hell (the ninth circle being transmission) called ‘turnaround’ – where a production company thinks it has gone as far as it can with a project and puts the rights back on the open market.

In the whacky world of television, it is fairly rare for a project put into ‘turnaround’ to be taken up again and brought to some sort of successful conclusion, but miracles do sometimes happen.

As Reg himself says: Even as wiseacres were still assuring me it would be at least five years before anyone else would come near the dynamic duo, the wonderful Eric Abraham of Portobello Pictures snapped them up within a couple of months and did a co-production deal with the BBC. The rest is history, and I am glad to say actuality.

With a level of efficiency rarely seen in television, the first of 23 (to date) episodes of Dalziel & Pascoe, starring Warren Clarke and Colin Buchanan, was broadcast in March 1996.

I was asked if I’d like to try my hand at a self-adaptation when the BBC series got under way, says Reg ruefully, but by then I’d seen how it worked even for the top people like Alan Plater and Malcolm Bradbury. Everybody wanted to put their ha’penn’th in! I couldn’t be doing with that; I’m a bred in the bone ivory tower man! So I said thanks but no. After a birth dogged with so many complications, the TV series is still going strong and the founder of the feast is stoically philosophical about it all. From an American website which bears his name, I reminded Reg of the quote: TV is too self-absorbed to enter into an equal partnership. You start close and cozy enough but soon realize you’re not getting your fair share of the duvet and one day you wake to find you’re lying at the very edge of the bed, totally exposed to the chill morning air. Now is the time to either get out of get philosophical.

When he had recovered from the shock of finding out that he had an American website, I asked if he still went along with that statement. I said that? Don’t remember, but certainly agree with it. Happily, I got philosophical. The changes TV has made to my characters don’t seem to bother my readers much so why should they bother me? It’s a very popular show, it’s brought a lot of people to the books and the money’s not bad either! But I’m still convinced that TV people are really leftovers from the Invasion of the Body Snatchers. They look like us, they sound like us, but their thought processes are totally alien!

It seems Reg Hill will be sticking to novels, news which will be greeted with audible sighs of relief from readers and publishers alike, and after the 21st Dalziel and Pascoe comes out, a new Joe Sixsmith novel in his lesser-known private eye series, The Roar of the Butterflies, will follow at the end of the year.

How does he do it? I mean, physically, what is the secret behind his prolific output? It seems there isn’t one: I really am very boring and it’s straight on to the old PC. No artificial stimulants, seven-per-cent solutions or communion with the spirits.

And what about other crime writers? Who did he read and admire when he was starting out? Michael Innes, Lionel Davidson, Geoffrey Household, Francis Clifford, Michael Gilbert, Julian Symons, Desmond Bagley, Donald Westlake and Evan Hunter. And now, if he reads crime fiction for pleasure? Michael Dibdin, Michael Connelly, Elmore Leonard, Lee Child, Val McDermid, Margaret Murphy, Andrea Camilleri, John Harvey and many more, but I can’t go on forever.

Are there any unjustly forgotten crime writers? Francis Clifford seems to have dropped out of sight completely and he was good. Geoffrey Household, apart from Rogue Male has also fallen off the screen. And what about crime writers justifiably forgotten? Reg is too much of a gentleman to comment.

His own reputation among the critics is assured and I put to him the conclusion reached by the late Ian Ousby, one of the most thoughtful (if under-valued) observers of the genre: “Ever since A Clubbable Woman, Reginald Hill has steadily explored the unlikely partnership between Dalziel and Pascoe, the one not just reactionary but unquenchably coarse, the other not just liberal but conscientiously progressive. The result has proved as satisfying as anything current British writing has to offer in showing how a fundamentally conservative form can be made to serve as a vehicle for alert social comedy and even sharp contemporary observation. Yet in his recent additions to the series Hill has also thought it necessary to add to his original pair of detectives by expanding the role of Pascoe’s wife, the feminist Ellie, and introducing Sergeant Wield, the closet homosexual. The implication is obvious: because male and married, Pascoe could no longer be relied on as the voice of modernity.”

His reaction was as thoughtful as you would expect: This was certainly never a conscious choice, nor when I examine it, an unconscious one. Insofar as Ellie and Wield are the voice of anything, that anything is clearly something Pascoe, being nether female nor gay, could be the voice of. But their appearance, or rather their expanded roles, derives simply from the fact that I find it hard to create one or even two-dimensional characters. For me to want to write about them, I need to understand them. The token wife or the token underling just making up the numbers doesn’t work for me. Result is I often find one of the major parts of my revision process is to make sure I’m not telling my readers more than they need to know about very minor characters! But Ian Ousby’s comment about using a conservative form to make, by implication, subversive statements, is well said. The flexibility of the form has been one of the main reasons why I’ve felt able to keep D & P going as long as they have. If all they could do was detective work, I’d probably have grown tired of them years ago!

*

I think I first met Reg Hill in 1990 at the launch of A Suit of Diamonds, an anthology to mark the 6oth anniversary of Collins Crime Club. He was tall, thin, fit and spry (he still is) and struck me as the genial, possibly slightly absent-minded professorial type (he still does).

Simply on first sight, and certainly within a minute’s conversation with him, it was clear that there was no way he was the model for Andy Dalziel. So could Reg Hill actually be the more sympathetic committedly liberal figure of Peter Pascoe? I’ll let Reg himself have the last word on that: I wish! True, we were very close once, but as the years went by we drifted apart. Now the bastard’s still in his thirties, fighting fit, has all his hair, and doesn’t have to get up a couple of times every night to have a piss. Mind you, I sometimes think that maybe Andy Dalziel is actually the picture Pascoe keeps in his attic!

|

|

| Webmaster: Tony 'Grog' Roberts [Contact] |