|

Capital Crimes

Rumours have reached me, even out here in the wilds of the Eastern Marches, that a Comic-Con style festival called Capital Crime is being planned for London’s West End in September 2019. The brainchild of Goldsboro Books supremo David Headley and writer and film producer Adam Hamdy, Capital Crime aims to attract 800 conventioneers (if that’s a word) to the three-day event which will also include ‘a unique social outreach initiative’, though I have no idea what that means.

It is, of course, not the first crime-fiction themed convention to hit the streets of London.

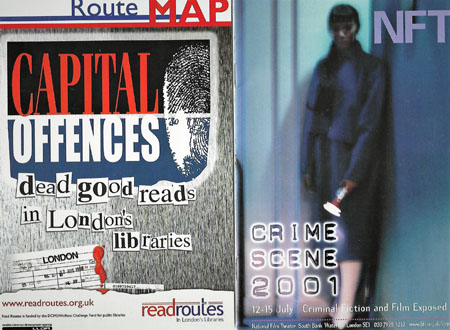

There was, for example, the Capital Offences ‘Read Routes’ initiative run by the London Libraries Development Agency in conjunction with the Crime Writers’ Association, which linked crime novels to London locations, produced an attractive map based on the underground network and organised multiple author talks in libraries.

Then there were the Crime Scene conventions at the National Film Theatre organised by Adrian Wooten on the film side and Maxim Jakubowski from Murder One.

Crime Scene, which ran I think for three years, attracted an all-star cast of actors, directors and writers (my one regret was not meeting Richard Widmark), offered a preview of John Hannah as Inspector John Rebus, Colin Dexter being put through his ‘Desert Island Hell’ and a performance of the now legendary quiz show I’m Sorry I Haven’t A Cluedo.

If Crime Scene had a drawback, it was that there was no central hotel where delegates could congregate, exchange pleasantries and debate. Some reprobates did however make an attempt to establish a forward base in one of the NFT’s refreshment areas, including Mark Timlin, Martina Cole and Russell James, as photographed by the young paparazzo Ali ‘Snapper’ Karim.

Film Fun

On a recent visit to Sicily, I learned something interesting about the art of making references to popular films and I do not mean all the t-shirts, mugs, ash-trays and tourist tat commemorating The Godfather on sale in Palermo (though the t-shirt featuring Homer Simpson as ‘Il Padrone’ was tempting.)

On an expedition to the newest craters on top of Mt Etna (to prove that an NHS triple bypass works at over 3000 metres), part of the journey was by cable-car and the Dowager Lady Ripster and I found ourselves sharing a car with a smart, middle aged couple sitting opposite. Looking out of the window at the ground disappearing below us, I followed the shadow of our car across the volcanic slopes and commented that the time to be worried would be when we saw the shadows of Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood fighting on top of the car.

As I said it, the couple sharing the car burst out laughing, having immediately got the reference to the film Where Eagles Dare, though I am sure neither were born when the film was released – or perhaps, being Americans from Colorado, they were just healthy.

Imagine then my surprise on returning to Ripster Hall (“Someone must have paid the ransom to Palermo” as one wag remarked) to find I had been sent a copy of Broadsword Calling Danny Boy, from Penguin, Geoff Dyer’s forensically funny critique and at the same time homage to the film based on Alistair MacLean’s 1967 thriller.

Literary critic Dyer, having admitted that the film of Where Eagles Dare (though not the book, which he describes as ‘unreadably bad’) made a lasting impression on him as a youth, goes through the film, deconstructing it scene by scene. The result is astute, clinical when pointing out the ridiculous bits (there are plenty), biting and also very rude about certain actors, particularly Richard Burton.

This is a short, almost biographical book, an essay really – not a rant, for there is genuine affection for the film – the sort of thing my old chum the late Jessica Mann would have called ‘a squib’ as she did when describing her rather good memoir The Fifties Mystique in 2012.

If I have a qualm about Broadsword Calling Danny Boy (which was to become a regular catchphrase of Jeremy Clarkson, though Dyer does not mention this), is that I cannot remember if the famous radio call-sign from the film was actually in the book. ‘Broadsword’ was certainly the code-name for the commandos sent where only eagles dared, but I don’t remember ‘Danny Boy’. It looks like I’ll have to re-read that ‘unreadable’ book.

Actually, I have a second qualm, not with Mr Dyer, but with Michael Ondaatje who, in a review, praises the author by saying “Who else would work in Martha Gellhorn…” (in a book about such a film …or book about thrillers)? Well, all I can do is refer him to footnote 7 of Chapter12 of the award-winning (have I mentioned that?) study Kiss Kiss Bang Bang [HarperCollins, 2017].

Coda

There is a coda to my cable-car/film reference story. On the return journey from Etna, sharing a car with two recently-graduated British university students, the topic of Sicilian drivers and their flamboyant approach to road safety came up. I remarked, quite wittily I thought, that the last scene of The Italian Job would, in Sicily, be taken as an example of perfect parking.

My remark was met with deathly silence, then one of the (British) graduates said: ‘Was that a film?’ and the other added ‘I think it was, but I’ve never seen it’.

To put it mildly, I felt rather old and to cheer myself up, dropped them off at a deserted crossroads on the outskirts of Corleone.

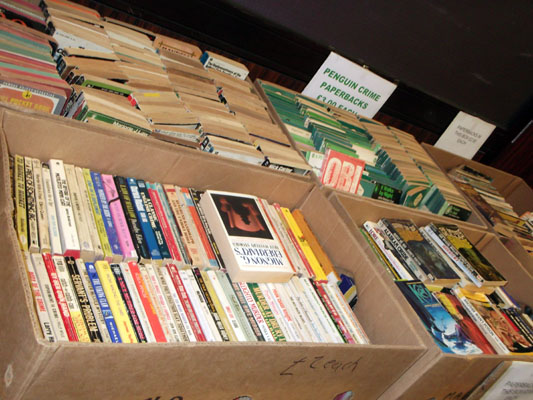

Pulp Fiction

The Paperback and Pulp Book Fair held in Bloomsbury last month was a magnet for comic collectors, sci-fi buffs and crime fiction devotees and I wandered the crowded shelves and groaning tables with one eye out for any of my books only to find none on sale. Whether that is a good thing or not I am not sure and even though I was not wearing my AUTHOR – WILL SIGN BOOKS FOR FOOD hat, I was recognised by more than one bookseller (and I spotted Christopher Fowler lurking over old maps of London in the ‘Ephemera’ section).

But this was very much a reader’s affair, not a writers and I was quickly drawn to the sections marked ‘Crime’. I was frankly amazed at the number and condition (mint) of sixty-year-old paperbacks on sale, and at the amount of them written by Mickey Spillane or Leslie Charteris. Several authors on my mental shopping list were, however, under-represented – Alan Williams, Francis Clifford, Victor Canning, P.M. Hubbard and – believe it or not, Dennis Wheatley – but I did manage to pick up three novels: one I have been meaning to read for several decades, one I knew of but had never seen before and one I had never heard of. There are no prizes for guessing which was which.

When chatting to my Australian colleague, that distinguished reviewer of crime fiction Jeff Popple, about the Pulp and Paperback Fair he mentioned that a similar book fair had been recently held locally to him, down under, and his prize purchase (hopefully at not too much of a bargain price) was:

.jpg)

Toasting Desmond

I was first informed of the discovery of an unpublished Desmond Bagley novel among the author’s archived papers, by Phil Eastwood who runs The Bagley Brief website. Naturally, on my next visit to HarperCollins, who will publish Domino Island in 2019, it was an excuse to celebrate, along with editors David Brawn and Chris Smith, the memory of a great, and much-loved, writer of adventure thrillers.

Written in the early 1970s and accepted by Collins – Bagley’s UK publisher – it is thought that Domino Island was put on the ‘back-burner’ by his American publisher so as not to clash with the release of the film The Mackintosh Man, based on Bagley’s spy story The Freedom Trap. For some reason, the author went on to a different writing project and never went back to Domino Island.

I have been treated to a sneak preview and will give you my thoughts next month, albeit about forty-five years late!

Vintage Corner

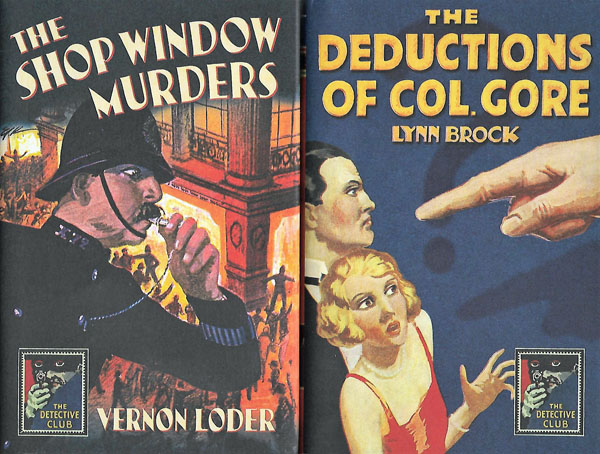

The latest reissues from the famous Detective Story Club in their attractive Collins Crime Club livery, are perfect examples of the ‘Golden Age’ of English crime-writing.

The Shop Window Murders, the shop in question being based on Selfridges (as the cover indicates), was a 1930 mystery by ‘Vernon Loder’ one of the several pen-names used by John George Hazlette Vahey (1881-1938). As the title suggests, two bodies are found in a department store window, one stabbed, one shot. A simple case of murder then suicide? Of course not.

There are some eyebrow-raising moments in the language used to tell the story – models ‘leaning in dégagé attitudes’, and characters called Miss Hoe (‘a woman journalist’) and the unfortunately-named Effie Tumour. Also (spoiler alert!) be wary of any character who smokes ‘Twix’ cigarettes, as these were distinctly lower class; though I could not help thinking of Colin Bateman’s ‘Mystery Man’ hero who is addicted to confectionery and would certainly have loved to light up a Twix.

The Deductions of Colonel Gore is an even earlier example (1924) of the ‘Golden Age’ by ‘Lynn Brook’, the pen-name of playwright Alexander Patrick McAllister (1877-1943), and it illustrates both the playfulness and the unsavoury attitudes of the era.

To be fair, the introduction does warn the 21st-century reader that they may find some of the references to Africans and Jews (women could be included too) which were commonplace at the time, slightly uncomfortable. Colonel Gore – ‘an epithet of Anglo-Saxon vigour’ – is back in England after running the colonies in Africa and living off a small inheritance. He quickly decamps for the west country having found himself ‘bored to extinction by a London which seemed to him entirely populated by Jews’. He regrets not following up a youthful romance with a young lady who now ‘has an income of a shilling a minute’ and thinks the ideal wedding present is a set of Masai head-dresses, masks and throwing knives dipped in poison. The best thing about Colonel Gore as a central character/hero is that he is a pretty awful detective and the title is clearly tongue-in-cheek as the deductions of Colonel Gore are not reliable and rarely correct.

|

|

Irish (and other) Eyes

Is the private eye novel making a comeback? Has it ever really gone away? Certainly there are some impressive examples around at the moment and leading the pack, as she has been since about 1982, is, of course, Sara Paretsky whose Shell Game [Hodder] came out last month, the nineteenth novel to feature her detective V. I. Warshawski, as played by the wonderful Kathleen Turner in a rather disappointing film.

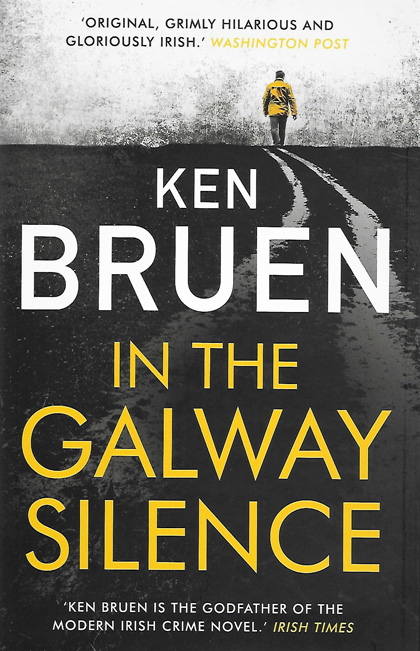

Ken Bruen’s Jack Taylor may not have been going quite so long, but he’s certainly going strong in his latest, In the Galway Silence published this month by Head of Zeus, in which, as usual, murder and mayhem as only the Irish can do it, interrupt Jack’s serious drinking time. (Breakfast tends to be coffee ‘with a base of Jay’).

Bruen has a unique voice in hardboiled fiction, his prose is poetic, scatological and spare to the point of making Hemingway seem verbose and overweight. His hero Taylor is haunted by past failures and relationships, and he has just as much trouble with the present. At times it as if the reader can hear the radio and television news programmes worming their way into Taylor’s brain, fuelling his rage at a world going, if not mad, then certainly downhill.

And then there’s Jack Taylor’s relationship with organised religion which, in Ireland with a character like Taylor, is never going to be a comfortable one, especially as part of the plot revolves around a paedophile. But even in the grimmest territory, Bruen can turn a wonderful phrase, such as: The road to hell is paved with well-intentioned nuns.

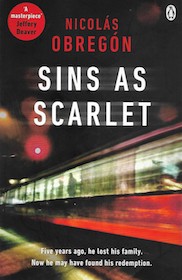

To prove that the private eye novel is versatile and its tropes adaptable to virtually location, time period and culture, then I offer Sins As Scarlet by Nicolás Obregón. For legal reasons I missed this when it appeared in hardback earlier this year, but the paperback is now published by Penguin.

Obregón was, I believe, born in Spain, lived in London then Japan and now resides in Los Angeles. He blends all his cosmopolitan experience into Sins As Scarlet, which features his Japanese detective Kosuke Iwata now working as a private eye in Los Angeles, but having brought much of his Japanese mental baggage with him. A specialist in finding missing persons very much in the old school style (knocking on doors, asking questions, calling in favours from police contacts), the stakes are raised when Iwata begins to investigate the murder of a young transgender male.

Sins As Scarlet is intelligently, often delicately, written. Not many private eye novels use words such as ‘mimesis’ or ‘repining’ – at least not accurately – and there is a haunting underlying sense of Iwata being a stranger in a very strange land, as is highlighted by a poster of Marilyn Monroe bearing the legend: Hollywood is a place where they’ll pay you a thousand dollars for a kiss and fifty cents for your soul.

So What Else is New?

It is a bumper month for fans of Wilbur Smith, the globe-trotting, mega-selling, big game hunting (and fishing) author of adventure stories for ‘real men’ (as he would say) for more than fifty years now.

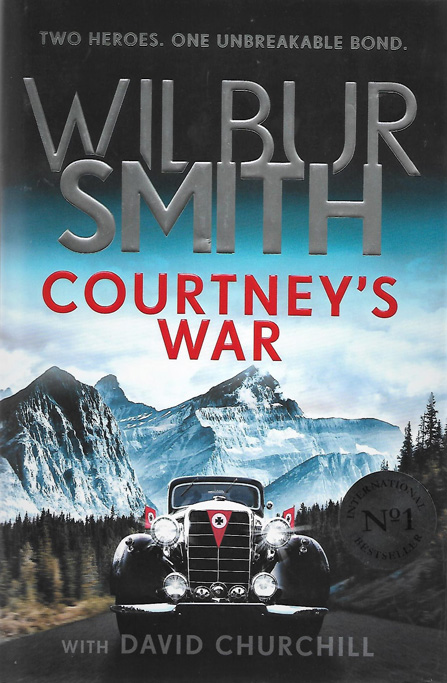

Bringing the best-known of his series up to date, or at least the second world war, Courtney’s War, written with David Churchill and published by Zaffre, is the seventeenth novel in Smith’s Courtney family saga.

The new novel comes with a promise that in 2019, King of Kings will combine two of Smith’s series – the Courtneys and the Ballantynes – in an adventure set in nineteenth century Egypt and Abyssinia.

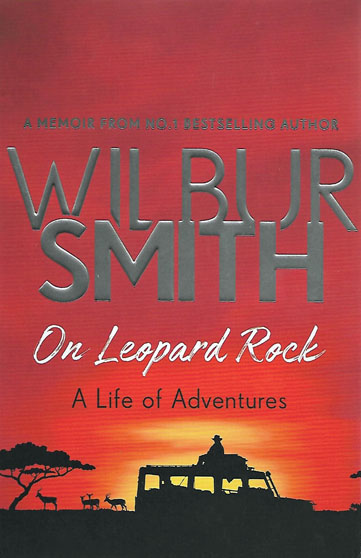

And if that wasn’t enough for any fan with a stocking to fill this Christmas, Zaffre have also published the paperback edition of Wilbur Smith’s memoir On Leopard Rock.

Most memoirs or autobiographies of successful thriller writers tend to be less revealing than their fiction, and this is no exception although there are plenty of stories about shooting lions (too many probably) and hunting in general, so that in one incident where Wilbur confronts a grizzly bear in Alaska, you can almost feel our hero itching to grab his famous rifle with all the notched ‘kills’ on the butt. Fortunately for the bear, Smith was, on this occasion, unarmed.

However, I did learn something I didn’t know; that Wilbur’s debut novel When the Lion Feeds was banned by the censors in his adopted South Africa and only published there eleven years after it had launched its author into the lifestyle of the super-rich.

An author who is almost exactly the same age as Wilbur Smith and still going strong, is Derek Robinson, who made his name with wartime aviation adventures (Goshawk Squadron) and then tricksy spy stories based on real events (The Eldorado Network), but has also written histories and non-fiction on topics ranging from rugby to his native Bristol.

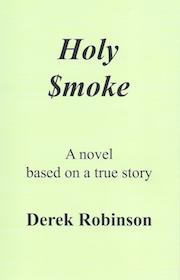

Derek has a new novel out, Holy Smoke, a wonderfully comic tale of deceit set in Rome in 1944, where the intelligence officers of the liberating American army are desperate for, well, any intelligence they can get. All too easily they fall for the spy fiction presented as fact by an unemployed, and very hungry, Italian journalist with ‘sources’ inside the Vatican.

It is a super read, enlivened by flashes of Robinson’s trademark cynicism and wit when it comes to bursting pompous balloons and given the author’s reputation for researching his subjects thoroughly, one wonders whether this tale is not all that far from the truth.

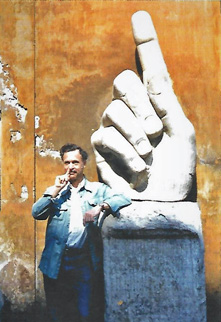

Derek Robinson, seen here in younger days in Rome suggesting a possible use for the finger of Constantine the Great, is not only the author of Holy Smoke, but also the publisher and copies are available only from him personally. His website (www.derekrobinson.info) gives all the details of where to send the required Postal Order, or whatever people do these days. Any true fan of wartime spy thrillers will find their £6 money well spent.

Years ago I predicted that American Michael Harvey was ‘one to watch’ on the basis of his excellent Chicago-based stories featuring private eye Michael Kelly, a character proud of his Irish heritage and fond of quoting classical Greek dramatists (a bit like his creator, I suspect). Novels such as The Third Rail and The Governor’s Wife were, I thought, first-rate although I admit to being less taken with Brighton where Harvey switched tacks and settings, to the Irish-American heartland of Boston.

Now it seems Michael Harvey has switched direction again, possibly into Stephen King territory, with Pulse, published by Bloomsbury, about a Boston teenager with strange, psychic(?) powers and some very unsavoury policemen. There is a lot of local geography (some names such as Mystic River being very familiar), plenty of gruesome killings and more loving detail about the game of baseball than any non-American reader requires. There is also a character called Mike Ripp. Coincidence? Almost certainly.

Another American author trying a new tack, a tack which I suspect will only increase his worldwide sales, is David Baldacci. His new thriller Long Road To Mercy, published this month by Macmillan, introduces a new female lead character (who certainly is destined for a series), FBI special agent Atlee Pine, initially working out in the very wild west. A case which involves a dead mule and a missing rider in the Grand Canyon and a serial killer in a ‘supermax’ prison in Colorado, could just put Atlee Pine on the trail of answers to why and how her twin sister Mercy (hence the title) disappeared, aged six, from their childhood home.

I am told that there is a new Lee Child novel out, but for legal reasons I know absolutely nothing about it…

In Short

I rarely get to read novellas, perhaps there are just not many of them around, so when two come along in rapid succession I sit up and take notice, especially when they are so good.

I mentioned Deon Meyer’s The Woman in the Blue Cloak last month and now this month comes The Drop by Mick Herron, from John Murray.

This is a real nugget of spy fiction, featuring many of Herron’s ensemble ‘Slough House’ cast of misfits, back-stabbers, front-stabbers and washed-up spies. One very washed-up agent features prominently here, as does an old, retired spy who is convinced he has seen a ‘drop’ take place, but surely such antique tradecraft is no longer practised. Of course it is, and things get really interesting when the recipient turns out to be a triple agent working for the German intelligence service (who are on our side, aren’t they?).

With outstanding cheek, Herron has the German ‘triple’ about to be ‘planted’ in that repository of sensitive secrets: the Brexit Office!

Overly Dramatic?

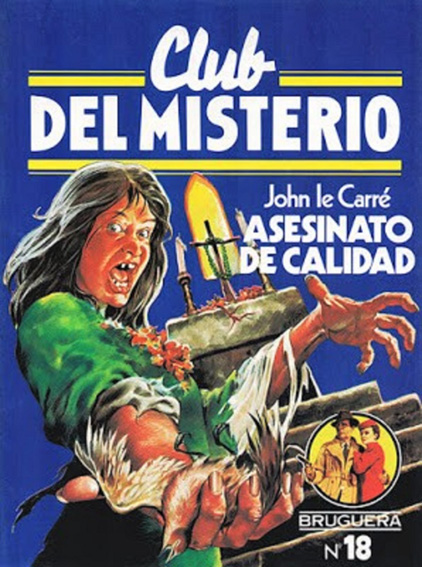

With all the hype surrounding the new television adaptation of John le Carré’s The Little Drummer Girl, my South American correspondent send me this cover from a Barcelona edition of one of the author’s earlier works, A Murder of Quality.

Now that was one cover too garish even for the Paperback Pulp Book Fair.

Toodles!

The Ripster

|