|

A Funny

Thing Happened

CrimeFest in Bristol was

great fun, cementing its reputation as probably the friendliest crime writing

convention around with attendees from as far afield as America, Iceland,

Norway, Italy and Yorkshire.

In

days of yore (technically the 1990s), the only convention for writers and

readers was the annual Shots on the Page

in Nottingham, where this outstanding organ was founded and from which it took

its title. In those days, as a national newspaper reviewer of crime fiction, I

was allocated the status of V.I.P. and allocated a Personal Protection Officer.

Now, decades later, I find myself classed as “elderly” (‘elder statesman’,

surely?) and therefore qualifying for a ‘Carer’ at public events.

In

Bristol, I was allocated Fraulein Catriona von Strupp, who dutifully helped me

on and off stage and cut my meat at formal dinners.

On

one of those stages I participated in a panel on comic crime writing chaired by

that cosmopolitan man of mystery Peter Guttridge and featuring the

irrepressible (God knows, we’ve tried) Ruth Dudley Edwards, Helen Fitzgerald

and Bernie Strachan (one half of the M.B. Vincent writing partnership).

There

were, as there always are, a number of pleasant surprises: meeting new people

(including Norwegians), old friends (Martina Cole, John Lawton, John Harvey,

Alison Bruce), helping an American reader track down copies of Bill Knox

novels, running into new writers who hadn’t actually registered for the

convention (you know who you are), and being appalled at the bar prices –

though no real surprise there.

It

was a particular pleasure to be surprised with a present in the form of a copy

of H.H. Kirst’s novel Death Plays the Last Card, a book

which I mentioned in this column two months ago, bemoaning the fact that I had

lost my original paperback copy and had failed spectacularly to replace it.

Such

generosity, let alone the proof that someone actually reads this column, should

not go unrecognised, but I will spare the gift-giver’s blushes and allow him to

remain anonymous. On a totally unrelated matter, I have a feeling that Quentin

Bates’ next mystery novel is likely to be worth a five-star review.

One

person I failed to meet was Finnish author Antii Tuomainen although I was

introduced to him, or rather his work, by his enthusiastic British publisher,

when she confronted me early one evening and threw down a gauntlet whilst

thrusting at me a copy of Palm Beach Finland from Orenda

Books.

Pointing

out that one of my distinguished reviewer colleagues had already described

Antii Tuomainen as ‘the funniest

writer in Europe’ (even though that does not narrow it down), her challenge to

me was that I should read Mr Tuomainen’s book and admit that it was the

funniest crime novel ever. When I

queried the cavalier use of the word ‘ever’ by invoking such names as Hiaasen,

Bateman, Pryce, Fforde, Caudwell, Brahms & Simon, Innes (Michael rather

than Hammond), Crispin, Swanson and Satterthwait not to mention anyone who

might have won the Last Laugh Award twice and be standing right in front of

them… I was told the challenge stood; nay, it would be a bet for a token sum. I

had no option but to agree as there was a member of Her Majesty’s Press on hand

to act as witness.

So

who won? Well of course I did. Palm Beach Finland, which for legal

reasons I missed when it first came out last year, is not the funniest crime

novel of all time. That’s not to say it isn’t amusing, with a wonderfully daft

setting – a dodgy seaside resort of sun, sand and palm trees in Finland – and some even dodgier

characters with obsessions about Eric Clapton and Alice Cooper. There are some

good gags, including a very rude one about Tiger Woods, but I do get the sense

that, just as Treebeard says ‘It takes a long time to say anything in Entish’,

it takes an awful long time to tell a joke in Finnish.

My

personal judgement should not of course put anyone off trying Palm

Beach Finland. A comic crime novel

from Scandinavia? Surely that alone is enough to start you chuckling.

Birthday

Party

It

was a pleasure to attend the annual birthday party thrown by the Margery

Allingham Society for the great writer herself, who would have been 115 years

old on May 20th this year.

The

small but dedicated society has enjoyed a fruitful year, with a successful

convention and visit to Margery’s former home in Essex, and has agreed to

continue its sponsorship of the short story competition it runs in conjunction

with the Crime Writers’ Association and CrimeFest.

The

guest speaker at this year’s birthday lunch, held at the University Women’s

Club deep in fashionable Mayfair, was Edwin Buckhalter, the former chairman of Severn

House, who now publish the ‘continuation’ novels featuring Allingham’s famous

sleuth Albert Campion. Apart from giving

an erudite and fascinating talk on Allingham’s skill as a novelist,

Edwin also performed the ritual cutting of the birthday cake.

Legal

Reasons

For

legal reasons I was unable to attend the lavish launch party for Thomas Harris’

long-awaited new thriller Cari Mora, nor have I actually seen

a finished copy of the book other than those being offered at half price in the

window displays of W.H. Smith, but I was treated to an advance proof copy about

a month before publication on condition that I signed a ‘legally binding’

non-disclosure agreement.

I

remember the same technique was used to promote the publication of the

disappointing Hannibal Rising some years ago and many reviewers, who should

have known better, got over-excited and felt because of the imposed secrecy,

the book must be both important and good. After all, Thomas Harris was the

author who created Hannibal Lecter – a Michelin-starred villain if ever there was

one – who had pushed the thriller into new, Baroque territory and possibly

invented the term ‘serial killer’.

Cara Mori is said to be the first Harris novel in

forty years not to feature Hannibal Lecter and it is probably tasteless to

admit that the old psychopath is sorely missed. His stand in, and a pale

imitation as a top villain, is Hans-Peter Schneider, a South American German

(no prizes for guessing his back story) who has his ghoulish moments, including

a portable liquid crematorium, particularly when peddling body parts to rich

clients more as trophies than medical replacements.

He

is up against Cara Mori, a beautiful (naturally) woman scarred by guerrilla

warfare in Nicaragua but seemingly able to take care of herself, although one

does get the feeling that the character is somewhat under-written. Certainly,

she’s no Clarice Starling and finds herself caught in the middle of the plot,

which is basically a Florida heist involving tons of gold bars hidden by a

drugs cartel, which has attracted rival gangs of treasure hunters. There is

plenty of gunfire ands deaths by pen-knife, exploding mobile phone and

salt-water crocodile; also a small cameo of gratuitous cannibalism which may,

or may not, be in homage to Dr Lecter.

It

is not that Cara Mori is a bad thriller, it is just not as good as Red

Dragon or Silence of the Lambs, but then how could it be? Given the

Florida setting, drug cartels and a supporting cast of none-too-clever heavies

and wise-guys, one feels that this is story Elmore Leonard could have done a

lot better, and Carl Hiaasen would have made much funnier, no doubt with an extended

role for the salt-water crocodile.

Proved

Right (Yet again)

I

noted last month that I was looking forward to the new thriller from Tim

Sebastian, Fatal Ally published by Severn House. I was not disappointed,

for it is, as I suspected, a cracking piece of spy-fi.

Sebastian

is a veteran television journalist and a former BBC correspondent in Moscow,

Warsaw and Washington, so has hung around many a corridor of power, keeping his

eyes and ears open. Not surprisingly the international power plays by various

security services have an awful ring of truth about them in a story which links

a Russian defector (a former British mole inside the KGB), a security advisor

to the White House, a plucky female MI6 officer and an American agent captured

by Isis fighters in Syria, as the action flits between Moscow, London,

Washington and the Middle East.

There

is a plethora of double-crossing, some explosive violence and a genuine feeling

of sympathy for the spies on the front line who put their private lives, and

actual lives, to one side in order to play the great game.

Fatal Ally also contains ‘the most brutal

obscenity in the Russian language’: Yob’

tvaya Mat. Now my Russian is rather rusty. Indeed I have not spoken it much

since those charming White Russian émigrés held such entertaining salons in Paris in the good old days,

but I do believe this could be a phrase later popularised by Mr Samuel L.

Jackson in many of his cinematic appearances.

Opening

Shot

Now

here’s a Chapter One opening you don’t see any more: Mike Allard was half-way through a tankard of keg bitter in a quiet pub

almost within sight and sound of Cambridge Circus when the girl came up to the

bar and perched on the red-topped stool next to him.

You

wouldn’t mistake that for a Raymond Chandler or a James Crumley opening, now

would you? The real giveaway being the ‘tankard of keg bitter’ which dates the

action, and the book, to the mid-Sixties. To be precise, 1965, when ‘keg beer’

(which had been around for more than twenty years) started to become

fashionable and that indeed was the year in which Striptease For Murder was

published as a paperback original by Consul Books.

‘Paul

Denver’ was one of several pen-names used by Manchester-based journalist

Douglas Enefer (1906-1987) who wrote more than forty pulpy thrillers for the

company World Distributors, which ran the Consul Books imprint from 1961 to

1966, including novelisations of television shows such as The Avengers and Cannon.

Striptease For Murder sees a

successful West End playwright involved in a frantic mystery which includes the

kidnapping in broad daylight of a leading Soho striptease artiste, a nuclear

scientist, a sinister doctor and a ‘thrill-seeking countess’, all of which our

theatrical genius seems to take in his stride. Is there something Alan Bennett

hasn’t been telling us?

Midsummer

Murders

Tell

the lawyers to stand down, this is not a misspelling of a famous television

show (supposedly the most popular crime drama in Denmark), but a new anthology

of ‘classic mysteries for the holidays’ from Profile Books.

Murder in Midsummer, edited by

Cecily Gayford is clearly aimed at fans of the so-called ‘Golden Age’ and

boasts contributions from Conan Doyle, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham,

G.K. Chesterton, R. Austin Freeman and John Dickson Carr (though the cover says

Carter Dickson). There is a smattering of more modern tales from Ruth Rendell,

Ellis Peters, Julian Symons and Michael Innes, though nobody actually…well,

alive.

For

readers who recognise this distinguished cast list, all well and good, though

most of the stories will already be familiar to them. What the anthology is

crying out for is an Introduction or some guidance notes to point – and I hate

to say the word – younger readers to

these authors. Dedicated ‘Golden Agers’ do not seem to realise how many famous

names to readers of my vintage elicit only baffled and blank looks from younger

generations.

At

the recent CrimeFest, at separate

events, it was clear that that the names Ellis Peters, Geoffrey Household

(FFS!) and Michael Innes meant nothing to the latest generation of readers and

the recent series of University Challenge

showed that the finest young minds could not identify characters created by

Margery Allingham nor Dorothy L. Sayers (the latter faux pas committed by an

Oxford College!).

If

for nothing else, Murder in Midsummer contains a Sayers’ story – The Unsolved Puzzle of the Man with No Face

– which has the marvellous line, when describing a system of organised crime

families in Italy as ‘a sort of Sodom and

Camorra’ which I like and will probably steal. But in the John Dickson Carr story featuring

the rather absurd detective genius Sir Henry Merrivale, the more politically

correct and sensitive (and, yes, younger) reader may be rather put off by the

way he addresses every female character as ‘wench’.

|

|

Books of the Month

Troubled detectives and cold cases coming back to haunt them are familiar tropes of modern crime fiction. Less common these days is making your detective a foreign national working in his (it’s usually ‘his’) native country, providing the reader with an insight into an exotic or unfamiliar setting. It is a long and honourable tradition when done well, from Harry Keating’s Inspector Ghote and Michael Dibdin’s Aurelio Zen, to more recent creations such as Martin Walker’s Captain Bruno and Peter Morfoot’s Paul Darac.

A very troubled detective and a cold case (perhaps not so cold) feature in The Copycat by Jake Woodhouse, published by Penguin, and as the former police detective Jaap Rykel is Dutch and the setting Amsterdam, we should enjoy this series while we can just in case a final Brexit cuts us off from Eurocrime as well as Europe.

As a hero, Rykel has many distinctive characteristics, apart from being well-aware of past mistakes. He lives on a barge (fair enough, in Amsterdam) and drives a far from inconspicuous Ford Mustang. Other fictional detectives, of course, have lived on houseboats and had distinctive modes of transport, but few that I can think of have (a ‘seven percent solution’ excepted) such a fondness for smoking substances which are not illegal in Holland. And Rykel seems to be something of a connoisseur of substances of every ilk.

Despite his intake, he keeps a clear head (mostly) when tackling a case of possible copycat killings whilst providing a running, rather salutary, commentary on the modern criminal underworld. In a powerful and suspenseful, somewhat hallucinogenic finale, Rykel finds himself naked and restrained by cable ties. Where would the modern crime novel be without cable ties?

I remember when John Grisham burst on to the crime scene in the early 1990’s and ushered in a new wave of American ‘legal thrillers’, although there were many in this country who fondly remembered Perry Mason. That particular sub-genre is still going strong and an excellent example is L.F. Robertson’s Next of Kin, out now from Titan Books.

Not only is this a well-written thriller but also an indictment of the American judicial system and its treatment of women, whereby a character has spent ten years on Death Row having been found guilty (though she’s not) of being an accomplice to murder.

Author Linda Robertson knows of what she writes as she is a practising defence lawyer in California who has, for the last twenty years, only handled death penalty appeals. She is also the co-author of the wonderfully titled The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Unsolved Mysteries, which sounds as if it should be required reading for all aspiring crime writers.

Without doubt the strangest book of the month is Kill Monster by Sean Doolittle, from Severn House, which starts with a flashback to ‘Bleeding Kansas’ in 1856, just before the American Civil War and a plan to assassinate some of the leading pro-slavery politicians. (And yes, I had to look up Atchison and Stringfellow; no, not that one.)

The plot, hatched by a preacher and a rabbi, is hardly subtle. Using Jewish lore and a fair bit of magic (don’t ask), a golem is created, a fearsome killing machine programmed to a specific victim. Unfortunately, en route to Kansas, the riverboat carrying the monster (packed in a crate marked ‘Books’) is wrecked and sinks. The course of the Missouri river changes over time and after 150 years, the golem is discovered and released. As his original victim is long-dead, the monster begins to hunt down blood relatives and it takes unearthly forces, and a motorcycle, to stop it. (A climax which, naturally, the present-day media dismisses as ‘Fake News’!)

It’s a bonkers, wild-ride cross-over between crime thriller and horror fantasy.

Far more down to Earth, though with a setting famous for its unworldly beauty is the exciting What Lies Buried by Margaret Kirk (Orion) which is a very good example of Tartan Noir, if I can use that expression for a very professional police procedural investigation set in the wild and lonely place which is the Highlands of Scotland. (Is it possible that we can expect a future division into Highland and Lowland Noirs, just as we have Island and Speyside malt whiskies?)

There’s much to enjoy in What Lies Buried apart from the scenery though, including some nice turns of phrase such as when describing a run-down cottage as having walls ‘the colour of three-day-old porridge’. In one spooky scene in a graveyard, a character identifies a strange carving as the symbol of ‘the goddess Eostre – witches, moon magic, that sort of thing’. I have to point out that Eostre, a deity of the pagan Germanic tribes we tend to call the Anglo-Saxons, was associated with Spring and a reawakening of the land after winter and from whose name we get the word ‘Easter’. In another spelling, Ostara, it is also the name of the small, boutique publisher which includes Top Notch Thrillers among its imprints.

Just thought I’d mention that.

It is hard to keep up with the floodtide of psychological suspense novels now lumped, perhaps unfairly, together in the sub-genre ‘Domestic Noir’. Three have caught my eye this month because of their accompanying promotional blurbs such as: You never know what’s going on behind closed doors; Three girls. One missing. One a murderer. One trying to find the truth.; and What if the people we trust are the ones we should fear?

They are, respectively: Who Killed Ruby? by Camilla Way (HarperCollins), Then She Vanishes by Claire Douglas (Penguin) and The Dangerous Kind by Deborah O’Connor (Zaffre).

A Deluge of Sherlocks

Most readers of crime fiction are aware that Sherlock Holmes had his imitators, but I suspect that few have any idea of just how many he had, and how quickly they emerged scrabbling at his coat-tails.

Fortunately, writer, editor and Victorian specialist Nik Rennison does and has produced another fascinating anthology of stories from ‘the golden age of gaslight crime’ – gaslight in this sense referring to street lighting rather than psychological manipulation as the young people would have it.

More Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, published by No Exit, contains a cornucopia of known names, unknown names and probably known unknowns. Among the authors featured: Ernest Bramah, Robert Eustace, E.W. Hornung, Baroness Orczy and R. Austin Freeman should ring a few bells, if faintly. Some of the rival detectives, though, may not. Dick Donovan, as created by Preston Muddock? Anyone? And what about police inspector Addington Peace, created by Bertram Fletcher Robinson (1870-1907)? Though to be fair, Robinson was a mate of Conan Doyle, who dedicated The Hound of the Baskervilles to him.

The collection will delight Sherlockians (if only by confirming their belief in the brilliance of the original) and also serious students of crime fiction history. I have only one quibble. Given that the period covered was roughly between 1895 and 1914, the cover shows a pair of flintlock pistols which were at least forty years out-of-date by then, except among duelling aristocrats in long Russian novels, and had been replaced by revolvers; and by the time these stories were written, cutting edge German technology, thanks to both Herr Mauser and Herr Luger, had developed the automatic pistol.

Odd Awards

Is it just me or has anyone else thought it odd that one of the titles short-listed in the 2019 Iceland Noir Awards is James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity which was first published in book form in 1943? Perhaps it has only just been translated into Icelandic.

And my other eyebrow was raised when I saw, on the Crime Writers’ Association’s list for their John Creasey Award for best first novel, Overkill by New Zealander Vanda Symon. Now I remember reading, and liking very much, Vanda’s third novel Containment when I was one of the international judges for the Ngaio Marsh Award in 2010. On checking, I discover that her debut novel was published in New Zealand in 2007 but has taken over a decade to find a UK publisher.

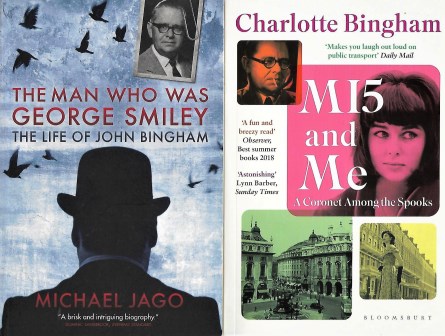

I am currently immersed in Michael Jago’s 2017 biography The Man Who Was George Smiley and Charlotte Bingham’s very funny memoir MI5 and Me.

My more astute, or at least awake, readers will have instantly made the connection to John Bingham (and his daughter Charlotte), one of our best, and also most neglected, crime writers in my not so humble opinion, right from his ground-breaking debut My Name is Michael Sibley in 1952 to his excellent spy story The Double Agent in 1966.

John Bingham (1908-88) the heir to an Irish barony was to become the seventh Lord Clanmorris. He was also a journalist and an officer in MI5 from 1940, and, at one point, the mentor of John le Carré as both an intelligence officer and as a debut author. (Hence the Smiley reference.)

I was inspired to find out more about John Bingham by Goldsboro Books in London when, as I was passing their impressive frontage, I noticed an al fresco display of second-hand paperbacks. Among the ‘pre-loved’ titles on sale, all at the bargain price of £3.50 (well, I said it was London) was a John Bingham novel I had not only not read, but not heard of before: I Love, I Kill, originally published in 1968.

It is a typical Bingham exercise in suspense, containing some of his trademark police interview scenes (Line of Duty eat your heart out) as one failed actor sets out to ruin another thespian for stealing the love of his life, by helping him become successful and then fanning the flames of celebrity burn-out, but the end result is murder. The first-person narrator telling the story does so almost as a confession to the reader, whilst trying desperately not to confess to the police.

The theatre was an unusual setting for Bingham and though the book was thought to have potential, with £300 hardback and £500 paperback advances, it was not considered ‘one of Mr Bingham’s best’ by the critics. Michael Jago’s biography also notes that there were last-minute fears before publication that one of the characters could, libellously, be identified as Richard Burton!

The book does have its problems, but anything by John Bingham is worth reading and I am looking forward to learning more about the man who thought John le Carré had let the side down by writing The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and who found his debutant daughter a job as a secretary in MI5 to keep her out of trouble in the Swinging Sixties. As Charlotte Bingham went on to become a bestselling author, it clearly didn’t work.

Love it, Hate it (Love it really)

I have always respected the opinions of John Norris, former bookseller and very knowledgeable fan of vintage crime fiction, and am a regular reader of his Pretty Sinister Books blog. Over the years we have agreed on many things, albeit John is an American, particularly some disgracefully forgotten authors such as P.M. Hubbard and John Blackburn, and disagreed on very little. Until now.

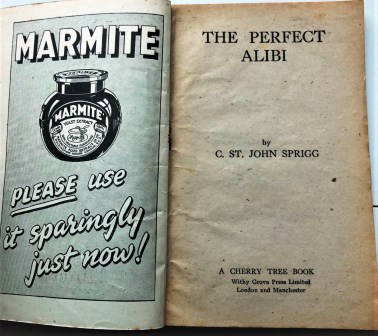

In recent blog posting, John wrote about

Cristopher St John Sprigg’s 1934 detective story The Perfect Alibi. Sprigg

(also known as Christopher Caudwell) is probably a better known for his short

(1907-37) but eventful life as a Marxist and British volunteer who died

fighting Franco in the Spanish Civil War, than he is for his handful of crime

novels, (he also wrote poetry criticism and on aviation) but those who have

read them do speak highly of them.

Given the positive nudge in John’s blog,

I am certainly tempted to try them, although I am outraged at the umbrage John

takes at the advertisement in his (wartime?) paperback edition for Marmite

which he describes – I suspect without trying at – as a horrid food product.

Well, I’m sorry, but

how very dare he? Boiled eggs with Marmite soldiers (or ‘peace workers’ as we

are supposed to say nowadays) is surely one of the great British comfort foods,

either for breakfast, a light lunch, a bachelor’s dinner or a late-night snack.

Indeed,

I used to frequent a pub in Norwich which had a very liberal interpretation of

the phrase ‘licensing hours’ where the landlady served all surviving customers

with boiled eggs and Marmite toast at 2 a.m. to indicate it was time we

they went home. True

story. The pub was called The Leopard

and it still exists, so if John Norris ever ventures across the Atlantic I will

insist on taking him there to sample the food of the gods, as we called it at

two o’clock in the morning, although I suspect late-night boiled eggs may no

longer be on the menu and Norwich Bitter is no longer 13p a pint.

Pip! Pip!

The Ripster.

|