|

The Land Beyond Bond

Is there a James Bond multiverse? I have no idea what that means, but it might become clear next month with the publication of a new James Bond novel which does not feature James Bond.

Double Or Nothing by creative writing lecturer Kim Sherwood [HarperCollins] and written with the blessing of the Ian Fleming estate, poses the question: how do you replace James Bond, who has been missing in action for more than a year? The answer is a triple substitute, with three ‘double-o’ agents stepping up to the plate: Johanna Harwood (003), Joseph Dryden (004) and Sid Bashir (009). It seems that Moneypenny has been promoted as well.

There’s a touch of the superhero about Bashir, who swiftly dispatches several enemies using knives in the opening chapters, and we learn of the private military contractors Rattenfänger, though it is clear that the real rat-catchers are the next generation 00-section.

There is also a dodgy tech billionaire, as there often is these days, who claims to be able to control the weather (and reverse climate change), with the resplendent name Sir Bertram Paradise, which got me wondering if it might have been a homage to the little-known 1968 thriller Counter Paradise by Nichol Fleming, Ian Fleming’s nephew.

The book was pushed in America as ‘007 for the under thirties’ but was rather overshadowed in the UK by the adventures of The Dolly Dolly Spy, though neither had anything like the staying power of the original Bond books.

Memories

After my mention of the death of much-loved crime fiction fan Bill Gottfried, I was contacted by many authors who also had pleasant memories of meeting Bill and his wife Toby at conventions and festivals in this country, and sent this photograph of the pair in London taken some ten years ago.

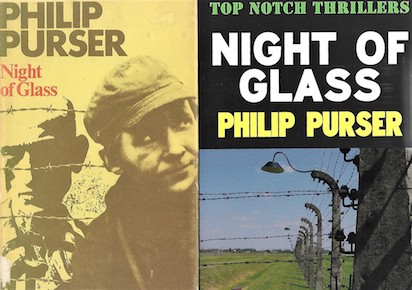

Yet more sober memories were evoked by the news of the death of Philip Purser, aged 95, best known as The Sunday Telegraph’s long-serving television critic but also the author of some interesting downbeat spy fiction, including a great thriller set in 1938 about a prison break (from Dachau concentration camp), Night Of Glass. It was a book I was delighted to republish as one of the very first Top Notch Thrillers in 2010.

Is the end nigh?

As the world seems to pass by me at a rapidly increasing rate, and Help The Aged envelopes have started to drop through the letterbox containing money, I have been thinking much about retirement of late. Partly this is due to suffering from PTSD (Proof Trauma Stress Disorder) due to the unprecedented number of advanced proofs of new crime novels sent by publishers this calendar year – 178 to date, including two of books not actually published until 2023.

One of those, which will be ‘first published’ in March 2023, is described as a debut novel which won the Bridport Prize for a First Novel in 2018 and then the Lucy Cavendish Prize for unpublished writers in 2021. I am confused; or maybe just tired.

Summer Summit

The stunning summer evening party to celebrate publisher Head of Zeus’ tenth birthday afforded a rare chance for the Harry, Hermione and Ron of the Shots team to get together for a serious editorial conference.

That took about thirty seconds and after a personal welcome from CEO Nic Cheetham, it was party on and a chance to catch up with some old acquaintances not seen since pre-Covid days and even mingle with some literary agents. Among the guests was archaeologist Francis Pryor and we soon bonded over matching linen jackets and a glass or two of bubbles, the conversation rapidly turning from publishing to the dark humour of digging archaeological sites littered with munitions from two world wars.

The Real Golden Age

The full title of Joan Lock’s non-fiction study is The Golden Age of Murder: Pistols, Bombs and Motor Bandits [Robin Books] but even that is not a full description of its contents. Essentially, the book looks at the emergence of the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of English detective fiction in the 1920s and compares the crimes depicted, or suggested, in it with what was really happening in the world of crime and policing at the time. Joan Lock, being a former police herself as well as an historian of British policing, being in the perfect position to do this.

Perhaps the most surprising thing is the fact that there were no murders in country houses in England in the 1920s and London (with a population of over eight million) was a pretty safe place in 1928 recording a mere 21 murders, a poor showing compared to the 404 in New York, though not if you ventured on to the roads where over 1200 deaths were recorded in traffic accidents.

It would have been interesting to know what the law on firearms was back then, given the large amount of weaponry available after the end of World War I, but there are fascinating nuggets about the real crimes rarely covered by ‘GA’ authors, such as horse-chanting and van-dragging and the gangs which terrorised racetracks (pace Graham Greene), though no Peaky Blinders as far as I could see. Joan Lock also recounts the failed attempt, in 1923, of a gang of Fenian terrorists to set fire to a Thameside oil refinery, despite it being located next to a gas works and a distillery – surely a worry for a health and safety inspector had there been one – and there are interesting sidebars on the Special Branch and raids on British Communist Party offices.

In terms of authors who insisted on the ‘play fair’ school of detective fiction, all the usual suspects are there, and there’s a nod to Margery Allingham who, in 1929, was ‘ahead of the curve’ in moving away from mechanical (if ingenious) plots and lifeless characters, despite her debut featuring an aristocratic amateur sleuth and a murder in a country house.

Cashing-in (in good way)

Ten years after winning the Crime Writers’ Association’s John Creasey New Blood Dagger for best first novel, and eight years after winning the CWA’s Gold Dagger, attractive new editions of Wiley Cash’s two prize winners have been published by Faber.

A Land More Kind Than Home and This Dark Road To Mercy have both been praised as fine examples of ‘Southern gothic’ and one reviewer likened This Dark Road to ‘Harper Lee by way of Elmore Leonard’. Praise indeed.

Stunning Impact

By rights, Impact by Mark Mills [Joffe Books] belongs in the ‘Books of the Month’ section but I wanted to write about it at more length, plus it is technically a book of last month as it was published in July.

The first thing to say is that it is extremely good, whatever the month, and something of a departure for Mark Mills who has chosen contemporary New England as the setting to introduce an impressive crime-fighting duo: the ambitious young detective Dylan Bodine and his reluctant mentor veteran police detective (and former FBI investigator) Carrie Fuller. There is genuine chemistry between these two characters and surely they are destined for a series – it will be a shame if they are not.

Impact begins with a failed assassination attempt (set up as a traffic accident) on a young woman who is about, though she doesn’t know it, to inherit control of a huge family fortune. As our police duo, sensing foul play from the off, track down a pair of hired killers, it becomes clear that someone inside the family is pulling the strings. One of the most satisfying crime novels I have read this year, both well plotted and well-written.

It is many years since I met with Mark Mills to declare myself a fan of his writing and particularly his historical thrillers such as The Savage Garden, The Information Officer and House of the Hanged, but Impact finds him abandoning Eric Ambler territory for the modern American mystery.

There is one particular line in it which struck a chord with me, when one character says, disparagingly, to another: ‘Did you get that from a book you bought in an airport?’

Given the context, there is nothing wrong with that sentence but it reminded me of my first visit to America, back in 1979, when I arrived at Heathrow and realised I had forgotten to pack a book to read on the flight. I immediately hit the nearest bookshop and, knowing nothing of the author and attracted solely by the cover, bought a paperback.

That thriller, which I still have, was Anthony Price’s The Alamut Ambush. I began reading as the plane took off and finished it as we landed at Chicago O’Hare. As I could not find any Price books in the US, I had to wait until I returned to England to buy the seven titles in paperback and then every subsequent one of his superb spy stories.

So I, for one, certainly did get something useful from a book bought in an airport.

Hands Down Regrets

It is with great regret that due to an overseas posting I will miss the launch party for Felix Francis’ new novel Hands Down [Simon & Schuster] next month.

A Francis launch, first for Dick, then for Dick and Felix, and now for Felix, is one of the endearing traditions of the London crime writing scene and usually marks the start of the Autmn ‘season’ of publishing parties. I have been privileged to have been invited to these most excellent parties since (I think) about 1991 and can remember only ever having missed two before now, so this will be me coming in a poor third.

I will, however, make sure I have a copy of Felix’s new thriller with me on my travels, especially as it features my favourite Dick Francis hero, Sid Halley.

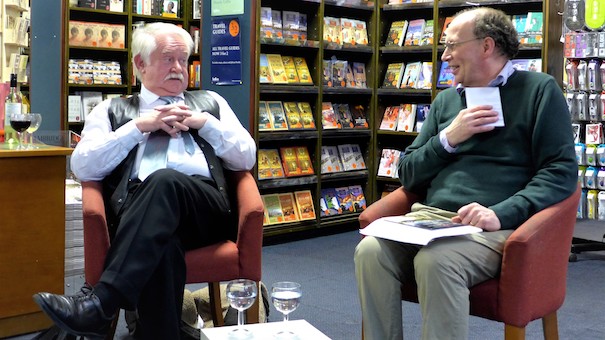

Sadly, I will also be unable to attend the farewell party for Richard Reynolds, who is leaving his post as crime fiction supremo at Heffers in Cambridge. A stalwart supporter of all crime writers, Richard’s Bodies In The Bookshop events were supremely friendly occasions despite dozens of crime writers each trying to push their own books on enthusiastic, though often overwhelmed, customers.

Richard also made Heffers a safe space for authors launching new titles and, as I can testify, was an interviewer who really did his homework.

|

|

Books of the Month

What should you expect from a good historical mystery? Well, a decent mystery, obviously, and interesting characters to guide you through the plot, plus some inside knowledge of a place or period in history you are unfamiliar with. The Lost Man of Bombay by Vaseem Khan [Hodder] ticks all those boxes, and probably more, with ease.

Set in 1950 in an India finally free from Imperial British rule, Persis Wadia struggles to prove that being the first female police inspector really is a suitable job for an Indian woman, though often the odds seem stacked against her, especially when lumbered with the case of a murdered white man found frozen in the foothills of the Himalayas. A tenuous link brings the body to Bombay, a place where it wasn’t so much a case of who casts the first stone, as cast the first stone before it is cast at thee, but almost before Persis can get her teeth into this very cold case, she has a fresh double murder on her hands and a particularly boorish superior officer to deal with.

Persis Wadia is a wonderful character, even if in danger of over-thinking her private life (and her father’s), never afraid to go it alone or tackle a cipher or code (something becoming a Khan trademark). Eventually she join the dots and solves the multiple murders, whilst avoiding being murdered herself. Along the way, the story is crammed with local colour and fascinating background on India’s legion of customs and religions as well as a nugget of history about POW camps in WWII of which I, for one, was totally unaware. So that’s another box ticked.

My favourite Michael Mann films are Manhunter and Last of the Mohicans, but his heist movie Heat is still the one most talked about, amazingly in these days of short memories considering it was released in 1995. There are currently rumours of a prequel based on the book Heat 2 by Michael Mann and Meg Gardiner, which was originally published four years ago in the US but now appears here from HarperCollins.

I’m not quite sure how much the book will appeal if you haven’t seen the movie, but film director Mann and that fine crime writer Meg Gardiner certainly make an exciting ‘high end’ crew.

Not strictly a crime thriller, but thrilling all the same, is Tick Tock by Simon May [Doubleday] which postulates the spread of a virus (?), a sort of tinnitus where victims hear a repetitive ticking in the ear, so loud other people can hear it too. The ticking becomes a countdown clock to deafness and death and whatever it is, it is spreading across the globe. Shades of John Wyndham here, with Mayo cleverly focussing his plot on an ordinary London school and its pupils and everyday problems such as getting to work on a tube full of panicking passengers.

Having just got through Covid, Mayo gives us another pandemic to scare the pants off us. Thanks a bunch, Simon.

A wise man once told me that there was spy fiction and then there was spy fantasy. Seventeen: Last Man Standing by John Brownlow [Hodder] is clearly in the latter category and might just have the impact Robert Ludlum’s ‘airport thrillers’ had half a century ago.

It begins as a spy story, with a classic ‘brush pass’ in Berlin and then the rather unsavoury removal of the crucial memory stick from the stomach of the courier who has swallowed it. This shouldn’t come as a shock as the first-person narrator is a professional assassin who has already killed six people by page 20, as he is number Seventeen in a line of assassins who follow some sort of creed which makes them available to the highest bidder.

The bulk of the book, though, is a long duel (it seems to go on for weeks) between Seventeen and number Sixteen in the assassin’s premier league, which takes place in the wilds of South Dakota and involves much weaponry, from rocket-launchers to chainsaws, and even an attack by a bear.

The body count is huge and the in-your-face narrative voice will not be to everyone’s taste. The enormous amount of stuff which Seventeen has access to, including a Bugatti Veyron or two, is incredible, but then this is turbo-charged, suspend-disbelief spy fantasy of the first order. It does, however, get Brownie points for use of the word petrichor – the first time I have ever seen that used in a thriller, and quite correctly too.

I was attracted to Alias Emma [Century] by the pen-name of the author, Ava Glass, as Glass is surname in my family tree and I did once consider writing under the name Raymond Glass, after an ancestor. I then found it rather spooky to discover a character called Charles Ripley in the book, though he turns out to be the head of a special unit of MI6 and not a Yorkshire miner as my grandfather Charles Ripley was.

The central character is the Emma of the title (though of course that’s not her name), a young agent tasked with escorting the target of a Russian hit squad to safety across London over one night. To make Emma’s life more difficult, the Russians have somehow got control of all the CCTV cameras in London, so Emma must ‘go dark’ and avoid being tracked by cameras or by her phone, and get across the city from Camden to Vauxhall without being seen, or killed.

For the most part, this is pacy, exciting stuff, though it is surprising how easily ‘facial recognition software’ can be fooled by pulling on a cheap wig and there are, conveniently, dressing-up boxes to be found along the way. The climax, in Paris, is a tad low key in comparison to the central hectic chase and there is a toe-curlingly touristy scene in the Red Lion pub in Parliament Street as a coda. (Spooks in Whitehall tend to avoid The Red Lion, much preferring to use The Two Chairmen on Dartmouth Street.)

There is a real treat in store for fans of the Mitchell and Markby series, sometimes known as ‘the Mitchell and Markby village’, by that most elegant writer of traditional English cosy mysteries, Ann Granger. Deadly Company [Headline], set in 2005, is a sixteenth book coda to the series which began in 1991, the last appearing in 2004, featuring Chief Inspector (now Superintendent) Alan Markby and his long-time girlfriend Meredith Mitchell.

Now approaching retirement and married to Meredith, Markby has established a home in a former vicarage in the Cotswolds. Being mistaken for the local vicar is the least of Markby’s worries when a body is found in the nearby graveyard – not an unexpected place to find body, but this one is not in a coffin and has been freshly murdered

Although by no means a conventional crime novel, The Girls Are Good [HarperCollins] by Ilaria Bernardini deals with a number of crimes (with a murder as a finale) in and among a team of young female gymnasts competing at a championship in Romania. The descriptions of the obsessive behaviour, the jealousy and the snobbery of the girls, overlaid by the cruel training regimes they suffer under, plus – as we know to our cost in this country – the inherent bullying and the opportunities for sexual predators in the sport, are all observed through the eyes of Martina, a member of the team but far from being one of its ‘golden girls’.

Spare and claustrophobic, Ilaria Bernardini, an Italian writing in English, generates a better sense of unease and impending doom than any three of the current crop of ‘domestic psychological suspense’ thrillers put together.

Podcasting into Print

I have never been a fan of ‘True Crime’ as I find it far too scary, nor have I ever knowingly listened to a ‘podcast’ (though I believe I have featured on one), but it seems that running a true crime podcast is the latest point-of-entry into a career in crime fiction.

This month sees the debut novel of the host of the true crime podcast Crime Junkie, American Ashley Flowers, All Good People Here [HarperCollins], which is co-authored by Alex Kiester.

In September, the co-host of the ‘chart-topping show Morbid: A True crime Podcast’ (it says here) Alaina Urquhart’s debut novel The Butcher and the Wren is published by Michael Joseph.

An autopsy technician by trade, Alaina Urquhart has degrees in criminal justice, psychology and biology and the podcast she co-hosts is said to have more than a million listeners and three million views on Tik Tok (whatever that is).From rumours within the book trade, this one is tipped to go straight from the morgue to the top of the bestseller lists, defying those who predicted, or hoped, that the craze for blood-thirsty serial killers was over.

What the Romans did for us

I am a long-standing fan of the ‘Roman’ novels of Scottish man of letters Allan Massie, which presented wonderfully sharp fictional biographies of the early Emperors, one of them (I forget which) basking in the nickname ‘the dinner gong’ because of the importance he placed on meal times.

Shamefully, I was unaware until I stumbled across one in a second-hand bookshop in the Charing Cross Road, that Massie had also written a series of thrillers set in Bordeaux during WWII and following the career of detective Superintendent Lannes.

Massie’s ‘Bordeaux Quartet’ began with Death in Bordeaux, published by Quartet in 2010, which is set in 1940 and subsequent novels follow Lannes’ story through to 1944, liberation and the end of the Vichy regime.

I am thoroughly enjoying my belated introduction to the quartet and actively hunting down the other three volumes.

I Spy Sherlock

With some trepidation I have accepted the honour of giving the Richard Lancelyn Green lecture to the annual general meeting of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London in October. [Green (1953-2004) was a leading Sherlockian scholar.]

I say trepidation because my knowledge of the Holmesian canon is poor, verging on the pathetic, so I will take as my subject the role of Sherlock as a spy and how he might have fared in British spy fiction in the period from Buchan to Bond.

I can claim one tenuous qualification for giving this lecture as, many years ago, I was presented with an honorary Sherlock Award for services to the now-defunct Sherlock magazine.

Last Word

For anyone not paying attention, I repeat that there will be no Getting Away With Murder column in September as I will be otherwise engaged. I will, however, take time out to raise a glass in memory of my great friend, the late Colin Dexter, who would have been ninety-two on the birthday we share on St Michael’s Day.

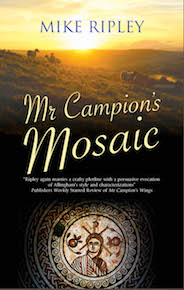

I will make sure my birthday celebrations, or the repercussions from them, do not interfere with the launch of Mr Campion’s Mosaic which is published by Severn House on 4th October.

Until October...

The Ripster.

|