|

RIPSTER REVIVALS #15

More ‘occasional’ ramblings having survived CrimeFest...

|

A Last Hoorah?

CrimeFest in Bristol was, as always a blast but rather poignant this year as it was billed as the last of these friendliest of crime writer/reader conventions and particularly for me as I was lucky enough to win the last Last Laugh Award for comic crime, after winning the first Last Laugh presented by the Crime Writers Association back in 1989. Fittingly (though he might not see it as an honour), I received the award from the current chairman of the CWA, Vaseem Khan, surely one of the hardest working crime writers around, who was the official Toastmaster for the event. And the light at the end of the tunnel is the distinct prospect that CrimeFest will re-emerge phoenix-like in a different form (but in the same spirit) in the future. I can say no more about that at this point, not because I would have to kill you if I did but because I simply don’t know any more, but I do live in hope.

Much of the fun of three-day events like CrimeFest (it is a marathon, not a sprint) is the chance to catch up on friendships made at previous conventions. In my case it was my annual opportunity to shoot the breeze with the likes of Alex Shaw, Paul Gitsham, Zoe Sharp, Christopher Huang, the delightful Ovidia Yu and the elusive Caro Ramsay, as well as making new chums and chumettes. But I have to admit that for an old trooper like myself, the greatest pleasure comes in meeting up with that motley crew I have been able to call friends for most of my crime-writing career.

My personal photographer managed to capture (or interrupt) me in greeting Lindsey Davis, whose fabulous novels of the underbelly of Ancient Rome I have reviewed with great pleasure since 1991; Denise Danks, the original ‘techno queen’ whose Georgina Powers thrillers I happily republished in new Ostara Crime editions in 2012 (and are now available as Joffe Books); and Quentin Bates, whom I hoped, as an honorary Icelander, would come in useful at Eurovision (he didn’t).

But it wasn’t all gossip and frivolity in the bar (although two of the hotel bars were successfully drunk dry). There were dozens of interesting panels, all well-attended, an impressive mass signing by authors contributing to the Leaving The Scene anthology (which goes on general sale in August), a video message from Jeffrey Deaver in America, notable appearances by Mark Gatiss, Matthew Sweet, Lee and Andrew Child and members of the family of the CrimeFest ‘Ghost of Honour’ John Le Carré, and the best off-the-cuff response by Felix Francis, as to what his wife thought of Fifty Shades of Grey (I hope Debbie doesn’t read this column).

Above all thanks must go (and I am unanimous in this) to CrimeFest organisers Donna Moore and Adrian Muller, for their dedication, generosity and sheer hard bloody work.

From the never-diminishing To-Be-Read Pile

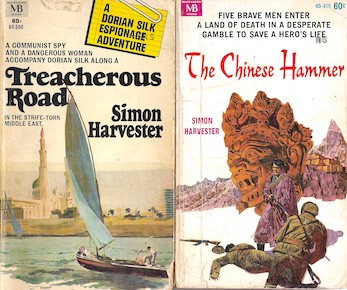

Legend has it that in the 1960s, the KGB station head in Kuala Lumpur used to place an order for multiple copies whenever he heard that a new Simon Harvester thriller was due to be published. The reason for his interest was that it would probably feature the further exploits of Dorian Silk, Harvester’s most popular fictional spy, a dedicated anti-communist and authority on just about every country south and east of Suez. Silk’s adventures were chronicled in a dozen or so novels between 1960 and 1976 and most had the word ‘Road’ in the title – Unsung Road, Battle Road, Moscow Road and, naturally, Silk Road – and were highly thought of in their day for their native detail and analysis of local politics. Edmund Crispin labelled them the ‘Asia in Turmoil’ series, although this was far from the author’s first series of popular thrillers.

Simon Harvester, the pen-name of Henry St John Clair Rumbold-Gibbs (1909-1995), was the author of more than forty novels, plus nineteen under the name Henry Gibbs and much non-fiction to boot. He began to write thrillers in 1942, invariably set in exotic locations, often with gifted amateurs co-opted in to some form of counter-espionage, and in 1960 launched two new spy heroes in overlapping series. His new protagonists were Dorian Silk, who was to feature in eleven books, and Heron Murmer, who sadly only made it into two.

I remember giving Harvester a go back in the day (almost entirely thanks to imported American paperback editions) and whilst intrigued by his insider knowledge of strange and distant lands, I was conscious even then that Harvester was guilty, very guilty, of over-writing and being rather economical with his action scenes. (Whenever guns are pulled, it’s usually just a single shot that does the job and fight scenes rarely last long.) With those caveats, it was with some trepidation that I decided to try the two battered Harvester paperbacks which have been in my To-Be-Read for far too many years. One of them even had a price sticker of 9p from a bargain bin at Woolworths!

Treacherous Road, originally published in 1966 at the height of the spy fiction boom, opens with Dorian Silk, on his fifth outing, in a scene unlikely to be found in a Bond book or film: he’s doing the washing up after a party though, to be fair, the party has taken place on a swanky houseboat in Cairo and had been thrown, naturally, by a beautiful woman with a hidden agenda which involves seducing our Dorian. In fairly short order, Silk is attacked knocked unconscious and staggers through the rest of the book with concussion(!).

He gets his new mission from Swann, his handler for British intelligence which seems to rely on gifted amateurs with local knowledge to be their agents, having lived through the scandals caused by Kim Philby, George Blake and Vassell, who are all name-checked. Silk is to accompany a former agent suspected of wanting to defect to the Russians or Chinese (or both, it’s not terribly clear) to Yemen, keeping his fellow traveller comatose by daily doses of sleeping pills.

There are some cringeworthy bits of social history – for instance, ‘Our ’Aarold (Wilson) and his bruvvers and Ted (Heath)’ and ‘London is terribly gay nowadays, what with the post office tower and other things’ – and the book is shot-gunned with Arabic words and expressions painfully rendered such as: ‘the old custom which has kept the true flowers of life from men at an hour when their sweetness should ensure every moment is memorable with its perfume.’

Apart from the KGB, the bad guy in all this is Egypt’s Colonel Nasser, for some reason is referred to as Nassah, who has planted troops in the Yemen where a lot of riding across the desert in jeeps takes place – oh, and another beautiful woman falls for Dorian Silk. To keep up with the craze for all things James Bond in the mid-Sixties, Silk is supplied with numerous gadgets, though nothing quite so flash as an Aston Martin with an ejector seat. Silk’s specialist equipment includes a secret radio and a silencer for his gun but to make sure you know these are secret gadgets, Harvester actually refers to them as the gadget radio and the gadget silencer. The ‘Q’ of the Bond films would have shaken his head in despair.

In the year Dorian Silk made his debut, 1960, Harvester launched his second fictional spy (who also had the under-used character Swann as his handler), Heron Murmer in The Chinese Hammer, set in another of the world’s trouble-spots, Tibet.

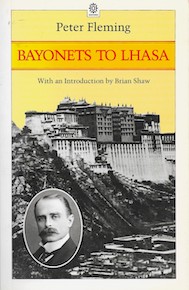

At the time, Harvester was not alone in spotting Tibet and the Chinese incursion there as a venue for some high adventure by men in arduous conditions; Lionel Davidson, Berkley Mather and Jack Higgins also had it pegged as a great setting. And Harvester seems to certainly know his setting with many florid descriptions of the Tibetan diet and local customs, peppered as you might expect with Tibetan terms, most of which are obvious without translation. What is far more confusing is the geography of the action which involves Murmer leading a small team of agents into Tibet to find the downed pilot of an experimental jet plane or rocket (it’s not terribly clear), collecting along the way as much intelligence on the Chinese invasion and Tibetan resistance. I am sure the geography as described is accurate but for a reader unfamiliar with Tibet, at least this one, it is rather confusing and I resorted to consulting the maps in Peter Fleming’s classic Bayonets To Lhasa, the story of the ‘Youngblood Mission’ of 1904, to get myself orientated.

At the time, Harvester was not alone in spotting Tibet and the Chinese incursion there as a venue for some high adventure by men in arduous conditions; Lionel Davidson, Berkley Mather and Jack Higgins also had it pegged as a great setting. And Harvester seems to certainly know his setting with many florid descriptions of the Tibetan diet and local customs, peppered as you might expect with Tibetan terms, most of which are obvious without translation. What is far more confusing is the geography of the action which involves Murmer leading a small team of agents into Tibet to find the downed pilot of an experimental jet plane or rocket (it’s not terribly clear), collecting along the way as much intelligence on the Chinese invasion and Tibetan resistance. I am sure the geography as described is accurate but for a reader unfamiliar with Tibet, at least this one, it is rather confusing and I resorted to consulting the maps in Peter Fleming’s classic Bayonets To Lhasa, the story of the ‘Youngblood Mission’ of 1904, to get myself orientated.

What was slightly weird, given Fleming’s nugget of British imperial history, was that in The Chinese Hammer, it is the invading Chinese who are repeatedly described as the imperialists.

For some reason Simon Harvester gave us only one further adventure featuring Heron Murmer (the now incredibly rare Troika in 1962), which I think a pity as I found him a much more interesting – more exciting – hero than Dorian Silk.

The Westheimer Express

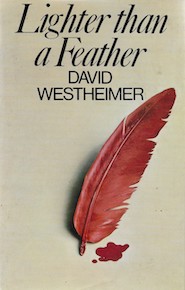

I cannot remember how or where I acquired Lighter Than A Feather, the 1971 novel by American David Westheimer, but I know I would have bought it because I had read the author’s most successful work, the wartime thriller Von Ryan’sExpress.

Westheimer (1917-2005) served in the US Army Air Force in WWII and on his twenty-ninth mission as a navigator on a Liberator bomber, was shot down over Naples in December 1942. He was to spend the rest of the war as a POW, first in Italy (clearly the inspiration for Von Ryan) and then in Stalag Luft III in Poland, the scene of the famous Great Escape. InLighter Than A Feather he stayed with a wartime theme, but switch from Europe to the Far East with an account of Operation Olympic, the invasion of southern Japan in November 1945 which, of course, never happened due to the dropping of atomic bombs and the surrender of Japan.

Westheimer (1917-2005) served in the US Army Air Force in WWII and on his twenty-ninth mission as a navigator on a Liberator bomber, was shot down over Naples in December 1942. He was to spend the rest of the war as a POW, first in Italy (clearly the inspiration for Von Ryan) and then in Stalag Luft III in Poland, the scene of the famous Great Escape. InLighter Than A Feather he stayed with a wartime theme, but switch from Europe to the Far East with an account of Operation Olympic, the invasion of southern Japan in November 1945 which, of course, never happened due to the dropping of atomic bombs and the surrender of Japan.

The massive amphibious attack on Kyushu, the most southerly of Japan’s main islands, is described in great detail from the point of view of the combatants on both sides, on land, in the air and on the sea, some of the most powerful passages dealing with the desperate attacks launched by Japanese Kamikaze aircraft and manned torpedoes. Written as one continuous narrative with no chapter breaks and littered with unfamiliar Japanese place-names, this is not an easy read as the action involves a cast of thousands (literally) and flits from one flashpoint to another.

The technique had been used to great effect on real events during WWII, as in the non-fiction accounts The Longest Day and Is Paris Burning? where the battles described were familiar, if only in outline. Lighter Than A Feather, whilst impressive in its research (Operation Olympic was planned in detail months before Hiroshima) and interesting in its concept, lacks that “what if?” factor of speculative alternative history because what actually did happen was so universally shocking that fiction simply couldn’t compete.

New Stuff

I rushed out to but a copy of The Einstein Vendetta by Thomas Harding (Michael Joseph) as soon as I read an early review of it, partly because it was a story I had not encountered before and the setting – Florence and its environs – was a place I have become very fond of over the years.

it was a story I had not encountered before and the setting – Florence and its environs – was a place I have become very fond of over the years.

In August 1944, only a day or so before the area was liberated by Allied troops, a unit of German soldiers crashed into the villa Il Focardo ten miles or so outside Florence demanding to see the owner. When he could not be found, his wife and two daughters were callously executed whilst he looked on from hiding in the surrounding woods. Was it a random act of gratuitous violence by retreating soldiers or did it have something to do with the family name: Einstein?

There is no doubt that what happened to Robert Einstein, a cousin of the slightly more famous Albert, was a personal tragedy and clearly a war crime, but it could it really be described as a ‘vendetta’ by Hitler against distant family members of the Jewish scientist he might have regarded as his nemesis, if he allowed himself such a thought (and in August 1944 he probably had a lot on his rather twisted mind)?

Robert Einstein was not a scientist contributing to the Allied war effort. He was not a combatant (though he was suspected of aiding local partisans) or a politician and not particularly interested in his Jewish heritage. Although born in Germany and having served in the German army in WWI, Robert had spent most of his life in Italy and he and his family had lived openly in the Florence area for eight years prior to the massacre. It seems that only when the end of German occupation was just around the corner that a troop of soldiers were actively hunting Robert Einstein and when they could not find him, they killed his family. Was it a hit squad with specific orders, and if so from whom? Or a gang of die-hard Nazis determined to participate in the final solution whilst they still had a chance? That it was a tragedy is not in doubt, doubly so when, less than a year later, Robert committed suicide.

The problem with trying to turn this tragic incident into a conspiracy is the weak spot of The Einstein Vendetta, but it is a fascinating story of how, over the years, many different people have attempted to apportion blame for the crime at the Villa Focardo, though many of the questions it raises are left simply hanging in the air. Which unit did the German soldiers belong to? (Witnesses could not say.) Who actually shot Mrs Einstein and the children? (There were no witnesses in the room where the killings took place, only perpetrators and victims.) What would have happened if Albert Einstein had gone to Italy to demand an investigation? (He didn’t.)

Still, attempts to identify the murderers continued into the twenty-first century, long after the likely killers had passed on out of judicial reach, and the killings at the Einstein villa and now honoured in a service of remembrance in Tuscany.

*

Still in Italy, but further south and more than 1,900 years ago, I am looking forward to the next Flavia Albia novel by my old chumette Lindsey Davis, who has personally sent me a copy of There Will Be Bodies [Hodder] when her publisher forgot to do so in April. The intrepid investigator takes on a case among the abandoned villas on the Bay of Naples which have been obliterated by the eruption of Vesuvius ten years previously. Working with her building contractor husband to restore a villa at Stabiae, Flavia and crew expect to find a few bodies among the ash and rubble, but not that of the previous owner. It is clearly a suspicious death and Vesuvius may not be the prime suspect.

I remember when Lindsey was in the Pompeii area researching the book, I recommended my favourite eatery in nearby Oplontis (Torre Annunziata if you insist on being modern) run by the splendidly hospitable Bolzano family, but I do not think she took up my suggestion as she was working and probably had no time for a four-and-a-half hour lunch.

*

And although he did not attend CrimeFest this year, I must make mention of the new novel by Andrew Taylor, A Schooling in Murder [Hemlock Press] which, on the surface, appears to have joined the swelling ranks of crime fiction set in or around WWII. Yet this is no bodies-in-the-Blitz thriller as it is set just after VE Day in 1945 in an evacuated girls’ school out in the western marches, where one of the mistresses has gone missing. It has a very spooky opening (spoiler alert) and just goes on getting spookier.

Beautifully written, as one would expect, this is an atmospheric crime novel already jostling for my totally unofficial Best of the Year awards. It is also paints a fascinating picture of a girl’s boarding school (not counting Malory Towers) and the best I have read in a mystery context since Agatha Christie’s Cat Among the Pigeons, where, if memory serves, I realised for the first time that Dame Agatha had a sense of humour.

*

And although, for legal reasons, I could not attend the lavish lunch which marked the occasion, I have been treated to an advance proof of Quantum of Menace [Zaffre in October], Vaseem Khan’s first ‘continuation’ in the James Bond universe which highlights the adventures of ‘Q’ the provider of gadgets and gizmos to 007, a.k.a. Major Boothroyd.

In the Bond films, the role of ‘Q’ was synonymous with the actor Desmond Llewellyn, whom I met on the set of The World Is Not Enough back in 1999. I had just seen on TV the 1950 film They Were Not Divided about a British tank crew in the latter stages of WWII and had somehow got it into my head that this was a sort of documentary and so I began to quiz Desmond, one of its stars, on his experiences in the tank corps. He answered my inane ramblings with polite patience, modestly declaring ‘it was just a role’. It was only sometime after that I learned that during the war, he had been captured at Dunkirk and remained a POW until 1945, having been confined in Colditz Castle following numerous escape attempts.

*

Still on a James Bond theme (of sorts), those wonderful people at Stark House Press in California have sent me a new title in their Black Gat imprint, presumably in advance of the inevitable Trump tariff. Its title – a uniquely silly one – Make With the Brains, Pierre was one I had never heard of and the name of the author, Dana Wilson, unfamiliar to me as a writer of mysteries, unsurprisingly as this appears to have been her one and only novel, first published in 1946.

Still on a James Bond theme (of sorts), those wonderful people at Stark House Press in California have sent me a new title in their Black Gat imprint, presumably in advance of the inevitable Trump tariff. Its title – a uniquely silly one – Make With the Brains, Pierre was one I had never heard of and the name of the author, Dana Wilson, unfamiliar to me as a writer of mysteries, unsurprisingly as this appears to have been her one and only novel, first published in 1946.

Contemporary reviews and subsequent re-evaluations seem to have rated it as a dark, psychological suspense story, reminiscent of the work of that master of the dark arts Cornell Woolrich, concerning Pierre Bernet, a French ‘film cutter’ in a dangerous love triangle (is there any other sort?) in 1940s Hollywood. But however intriguing the plot, the story behind the author is, in many ways, the book’s unique selling point.

Dana Wilson was born Dorothy Natoli in New York in 1922 and after high school, enrolled in drama school where she met and married fellow student Lewis Wilson, with whom she had a son, Michael. Moving to Los Angeles, the couple tried their luck in the movies with some success, Lewis having the distinction of being the first actor to play Batman on screen in 1943. Dana began to contribute to Hollywood scripts and retained her contacts within the film business as her acting career faded and she and Lewis Wilson divorced and she met producer Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli. They were married in 1959 and had a daughter, Barbara. The connection of Barbara Broccoli and her step-brother Michael Wilson was to become legendary in the context of the James Bond film franchise, although their mother Dana was said to make valuable contributions to many of the films and to have been instrumental in the casting of Sean Connery and later, Timothy Dalton, as Bond.

*

When my early ‘Angel’ books appeared in the last century, I was described as ‘destined to become a cult’ by (wouldn’t you know it) The Guardian and so I am naturally drawn to a ‘Cult Classic’ never before published in the UK, although the author was born in Yorkshire.

Nicola Griffith now lives in America where her crime novels featuring Aud Torvingen were first published and where she is, I think, better known as a sci-fi author. Described as ‘a rangy six-footer with eyes the colour of cement and a tendency to hurt people who get in her way’ Aud has also been considered (by Lee Child) as a possible sister for Jack Reacher. The first of three Torvingen thrillers, The Blue Place, is published in July by Canongate, along with the second and third instalments: Stay and Always.

My Most Vulnerable Spot

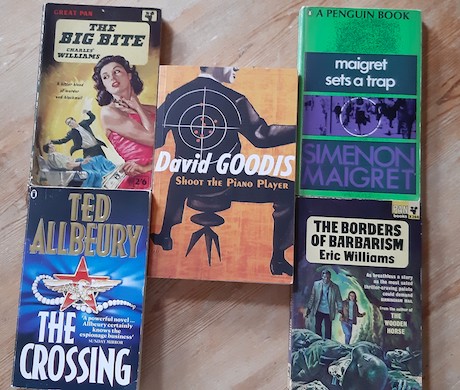

My bespoke (book) dealer knows my weaknesses well and just as my To-Be-Read pile showed some small sign of diminishing, he has sent me another batch of vintage paperbacks to shore it up.

I cannot say that any of these will prove a burden when I get round to reading them. The Eric Williams and the David Goodis are famous titles which I should have read but have not. The Maigret is from my favourite period of Simenon stories, the 1950s, and any Ted Allbeury is worth a place on my creaking bookshelves. The only slight doubt I have is on the Charles William’s book as, being a fan for many years, I thought I had read them all and perhaps I have read this one as his publishers here and in the US were far too fond of retitling his novels. Whatever, I am sure I will enjoy it.

As was said at CrimeFest:

‘Until the next time’...

The Ripster.